In this chapter from Self-Direction in Adult Learning (1991), Ralph G. Brockett and Roger Hiemstra argue that self-direction in learning refers to two distinct but related dimensions: as an instructional process where a learner assumes primary responsibility for the learning process; and as a personality characteristic centering on a learner’s desire or preference for assuming responsibility for learning.

contents: introduction · self direction in adult learning: a misunderstood concept · instructional method or personality characteristic? · self-direction in learning as an umbrella concept · the pro model: a framework for understanding self-direction in adult learning · conclusion

In introducing Self-Direction in Adult Learning: Perspectives on Theory, Research, and Practice Brockett and Hiemstra write as follows:

Few topics, if any, have received more attention in the field of adult education over the past two decades than self-directed learning. Ever since the 1971 publication of Allen Tough’s seminal study, The Adult’s Learning Projects, fascination with self-planned and self-directed learning has led to one of the most extensive and sustained research efforts in the history of the field. During the same time, a host of new programs and practices, such as external degree programs and computer and video technologies, have gained enthusiastic support from many segments of the field. The time seems appropriate for drawing some meaning from all of these theory, research, and practice developments.

Self-Direction in Adult Learning was their attempt ‘to make sense out of this body of knowledge and array of practices that have done so much to shape the current face of adult education in North America and, indeed, throughout much of the world’.

This chapter sets out some key theoretical understandings of the notion.

Ralph G. BrockettRalph G. Brockett is Professor in Adult Education, the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN. He holds B.A. and M.Ed. degrees from the University of Toledo and a Ph.D. in Adult Education from Syracuse University where he focussed his doctoral research on self-directed learning and initiated an innovative weekend scholar masters in adult education program. A past President of the Commission of Professors of Adult Education, Brockett has also served professorial roles at Syracuse University and Montana State University. He has published widely, including receiving an annual adult education book award. He also served as senior editor of New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education for a number of years.

Roger HimstraRoger Hiemstra is Professor and Chair, Adult Education, Elmira College. He was inducted into the International Adult and Continuing Education Hall of Fame in 2000. His books include Lifelong Learning (1976), Self-Direction in Adult Learning: Perspectives on Theory, Research, and Practice (1991), Environments for Effective Adult Learning (1991), and Overcoming Resistance to Self-Direction in Learning (1994), and Professional Writing (1994).

links: the full text of the book, plus a range of other useful material can be found on Roger Hiemstra’s website. See, also, the discussion of self-direction in the encyclopedia of informal education

Self-direction in learning is a way of life. This idea, which served as the backdrop for Chapter One, may be self-evident to many readers. Yet, much of what we do as educators of adults runs contrary to this basic idea. The myths presented in Chapter One illustrate some of the ways in which we, as educators, sometimes misunderstand or misuse our roles in a way that may run contrary to this “way of life.” It is our view that much of this misunderstanding and misuse is due, in large part, to confusion that exists relative to what is meant by self-direction in adult learning.

In this chapter, we work to alleviate some of this confusion by providing a conceptual framework that can help to clarify the concept of self-direction relative to the process of adult learning. We begin by looking at various ways in which self-direction and related concepts have been defined. We then offer our own definition of self-direction in adult learning. Finally, we share a conceptual framework that emphasizes distinctions between self-directed learning as an instructional method and learner self-direction as a personality characteristic.

Self direction in adult learning: a misunderstood concept

As with so many of the ideas found within the study and practice of adult education, self-direction in learning is fraught with confusion. This confusion is compounded by the many related concepts that are often used either interchangeably or in a similar way. Examples include self-directed learning, self-planned learning, self teaching, autonomous learning, independent study, and distance education. Yet these terms offer varied, though often subtly different, emphases. To illustrate these differences, several views of self-direction can be compared and contrasted.

An Early View of Self-Education. In the 19th Century, Hosmer (1847) described self-education in the following way: ” The common opinion seems to be that self-education is distinguished by nothing but the manner of its acquisition. It is thought to denote simply acquirements made without a teacher, or at all events without oral instruction–advantages always comprehended in the ordinary cause of education. But this merely negative circumstance, however important, . . . is only one of several particulars equally characteristic of self-education . . . . Besides the absence of many, or all of the usual facilities for learning, there are at least three things peculiar to this enterprise, namely: the longer time required, the wider range of studies, and the higher character of its object.” (p. 42)

A Lifelong Learning Perspective. It is important to think of self-direction in learning from a lifelong learning perspective. Lifelong learning, as will be noted in Chapter Eight, is not the exclusive domain of adult educators; it refers to learning that takes place across the entire lifespan. This view is supported by Kidd (1973) in the following passage: “It has often been said that the purpose of adult education, or of any kind of education, is to make the subject a continuing, ‘inner-directed’ self-operating learner.” (p. 47)

Another way of looking at self-directed learning has been provided by Mocker and Spear (1982). Using a 2 X 2 matrix, based on learner vs. institution control over the objectives (purposes) and means (processes) of learning, Mocker and Spear identify four categories comprising lifelong learning: formal, where “learners have no control over the objectives or means of their learning;” nonformal, where “learners control the objectives but not the means;” informal, where “learners control the means but not the objectives;” and self-directed, where “learners control both the objectives and the means” (1982, p. 4).

Self-Directed Learning and Schooling. Looking at self-direction as it relates to schooling for young people, Della-Dora and Blanchard (1979) offer the following view: ” Self-directed learning refers to characteristics of schooling which should distinguish education in a democratic society from school in autocratic societies.” (p. 1)

However, in describing the nature of self-education, Gibbons and Phillips (1982) offer a different view of self-education and schooling: ” Self-education occurs outside of formal institutions, not inside them. The skills can be taught and practiced in schools, teachers can gradually transfer the authority and responsibility for self-direction to students, and self-educational acts can be simulated, but self-education can only truly occur when people are not compelled to learn and others are not compelled to teach them–especially not to teach them a particular subject-matter curriculum. While schools can prepare students for a life of self-education, true self-education can only occur when a person chooses to learn what he can also decide not to learn.” (p. 69)

This second view reinforces the idea of learning as a lifelong process. Though the focus of this book is on self-direction in learning during adulthood, it is important to recognize that self-direction is not restricted solely to learning in the adult years.

A Learning Process Perspective. Self-direction in adulthood has often been described as a learning process, with specific phases, in which the learner assumes primary control. Tough (1979), for instance, has emphasized the concept of self-planned learning. His research was concerned with a specific portion of the process: the “planning and deciding” aspects of learning.

Using the related concept of the “autonomous learner,” Moore (1980) has described such an individual as one who can do the following: “Identify his learning need when he finds a problem to be solved, a skill to be acquired, or information to be obtained. He is able to articulate his need in the form of a general goal, differentiate that goal into several specific objectives, and define fairly explicitly his criteria for successful achievement. In implementing his need, he gathers the information he desires, collects ideas, practices skills, works to resolve his problems, and achieves his goals. In evaluating, the learner judges the appropriateness of newly acquired skills, the adequacy of his solutions, and the quality of his new ideas and knowledge.” (p. 23)

Still another view of self-direction that stresses the phases of a learning process has been offered by Knowles (1975). His view has been perhaps the most frequently used in the adult education literature to date: “In its broadest meaning, ‘self-directed learning’ describes a process in which individuals take the initiative, with or without the help of others, in diagnosing their learning needs, formulating learning goals, identifying human and material resources for learning, choosing and implementing appropriate learning strategies, and evaluating learning outcomes.” (p. 18)

An Evolving Perspective. Not only do individuals differ in their views of self-direction in learning, but each individual’s view is likely to change over time. Thus, when considering definitions, it is not only necessary to understand who has offered a particular definition, but when it was offered. This evolutionary process can be illustrated through the writings of Stephen Brookfield. For example, in 1980, Brookfield used the term “independent adult learning” to describe a process that takes place in situations “when the decisions about intermediate and terminal learning goals to be pursued, rate of student progress, evaluative procedures to be employed, and sources of material to be consulted are in the hands of the learner” (1980, p. 3).

Subsequently, as Brookfield began to contribute his ideas about self-direction to the North American adult education literature, the term “self-directed learning” started to appear in his writing. In using this term, Brookfield (1984c) noted the need to recognize differences between “learning” and “education.” Citing various authors who had addressed this distinction (e.g., Jensen, 1960; Verner, 1964; Little, 1979; and Boshier, 1983), Brookfield noted that learning has been used alternately to describe “an internal change in consciousness . . . an alteration in the state of the central nervous system” as well as “a range of activities . . . . equivalent to the act of learning” (p. 61). In this view, the former is used interchangeably with learning while the latter is used in a way similar to education.

Most recently, Brookfield (1988) has expressed this concern about semantic ambiguity to the extent that instead of using the term “self-directed learning,” he is “reverting to talking about the complex phenomenon of learning (as an internal change of consciousness) and making a distinction between this phenomenon and the educational setting or mode in which such learning occurs” (p. 16). While some may disparage writers who make such drastic changes in stance over time, we applaud Brookfield’s effort since, although we do not agree with his recent view that the adult education field should abandon its enthusiasm for the concept of self-directed learning, Brookfield demonstrates a willingness to accommodate new insights and information and to modify his position accordingly. Indeed, the conceptual framework presented later in this chapter reflects the evolution of own thinking about self-direction over the past several years.

Instructional method or personality characteristic?

As has been noted earlier, most efforts to understand self-direction in learning to date have centered on the notion of an instructional process in which the learner assumes a primary role in planning, implementing, and evaluating the experience. Yet, this view becomes weakened when considered in relation to semantic and conceptual concerns such as those raised by Brookfield. One of the first authors to address the confusion over the meaning of self-directed learning was Kasworm (1983), who stated that self-directed learning can be viewed as a “set of generic, finite behaviors; as a belief system reflecting and evolving from a process of self-initiated learning activity; or as an ideal state of the mature self-actualized learner” (p. 1). At about the same time, Chene (1983) addressed the concept of autonomy, which she largely equated with self-directed learning. In this article, Chene distinguished between two meanings of autonomy, where one view is psychological and the other “is related to a methodology which either assumes that the learner is autonomous or aims at achieving autonomy through training” (p. 40).

Clearly, the concern over what is meant by self-directed learning is a relevant one. Take, for example, the researcher who is interested in studying self-directedness as an internal change process, but who operationalizes self-directed learning as an instructional process. While there are definite similarities between the two concepts, the ideas are not the same. In fact, as will be noted in Chapter Four, this has been a problem in much of the research on self-direction conducted to date.

During a period of about one year, three authors tried to clarify the meaning of self-directed learning. Brookfield (1984c), as was noted earlier, used an argument presented by Boshier (1983) to point out that ambiguity of the term self-directed learning might be linked to confusion between learning (an internal change process) and education (a process for managing external conditions that facilitate this internal change). In this view, the term “self-directed learning” might best be reserved for the former while the latter would actually be viewed as “self-directed education.”

At about the same time, Fellenz (1985) made a distinction between self-direction as a learning process and as an aspect of personal development. According to Fellenz, self-direction can be viewed in one of two ways: “. . . either as a role adopted during the process of learning or as a psychological state attained by an individual in personal development. Both factors can be viewed as developed abilities and, hence, analyzed both as to how they are learned and how they affect self-directed learning efforts.” (1985, p. 164)

In building the link between self-direction and personal development, Fellenz draws from such concepts as inner-directedness (Riesman, 1950), self-actualization (Maslow, 1954), locus of control (Rotter, 1966), autonomy (Erikson, 1964), and field independence (Witkin, Oltman, Raskin, & Karp, 1971).

A third effort to clarify the concept of self-direction was made by Oddi (1984, 1985), who reported the development of a new instrument designed to identify what she refers to as “self-directed continuing learners.” The Oddi Continuing Learning Inventory (OCLI), a 24-item Likert scale, grew out of Oddi’s concern over the lack of a theoretical foundation for understanding personality characteristics of self-directed continuing learners. The development of this instrument, which will be discussed more fully in Chapter Four, was an outgrowth of the need to distinguish between personality characteristics of self-directed learners and the notion of self-directed learning as “a process of self-instruction” (Oddi, 1985, p.230). This distinction is not unlike the one made by Chene (1983) relative to the concept of autonomy.

In a subsequent article, Oddi (1987) distinguished between the “process perspective” and the “personality perspective” relative to self-directed learning, suggesting that the process perspective has been the most predominant in discussions of research and practice to date. As will be shown later in this chapter, this distinction between process and personality perspectives lies at the heart of the model we will present.

Finally, Candy (1988) has offered further support for a distinction between concepts. In a critical analysis of the term “self-direction” through a review of literature and synthesis of research findings, Candy concluded that self-direction has been used “(i) as a personal quality or attribute (personal autonomy); (ii) as the independent pursuit of learning outside formal instructional settings (autodidaxy); and (iii) as a way of organizing instruction (learner-control)” (p. 1033-A). Thus, Candy is essentially taking the distinction even further by differentiating between the learning process taking place both within and outside of the institutional setting.

Clearly, the concept of self-directed learning has undergone close scrutiny over the past several years. What has emerged is an important distinction between the process of self-directed learning and the notion of self-direction as a personality construct. This distinction needs careful consideration if we are to move ahead with the study and practice of the phenomenon.

Self-direction in learning as an umbrella concept

As we have noted, the idea of self-directed learning has undergone considerable evolution over the past several years. Indeed, this evolution can sometimes be seen in the case of a single author, as has been the case with Brookfield. It can also be seen in the subtle changes resulting from the research of many individuals over several years. Like Brookfield’s, our own notions of self-directed learning have evolved over time. The following two definitions are indicative of our earlier thinking about the concept: ” Self-planned learning-A learning activity that is self-directed, self-initiated, and frequently carried out alone. (Hiemstra, 1976a, p. 39) And “Broadly defined, self-directed learning refers to activities where primary responsibility for planning, carrying out, and evaluating a learning endeavor is assumed by the individual learner.” (Brockett, 1983b, p. 16)

Unlike Brookfield, however, instead of advocating movement away from the concept, we embrace the view that what is needed is to expand the concept and to encourage its continued development as a central theme in the field of adult education. However, it is our belief that in doing this, we need to move away from overemphasis on the term “self-directed learning.” Instead, given the confusion over self-directed learning as instructional method versus personality characteristic, we suggest that the term self-direction in learning can provide the breadth needed to more fully reflect current understanding of the concept.

In our view, self-direction in learning refers to two distinct but related dimensions. The first of these dimensions is a process in which a learner assumes primary responsibility for planning, implementing, and evaluating the learning process. An education agent or resource often plays a facilitating role in this process. This is the notion of self-directed learning as it has generally been used identified in the professional literature. The second dimension, which we refer to as learner self-direction, centers on a learner’s desire or preference for assuming responsibility for learning. This is the personality aspect discussed earlier. Thus, self-direction in learning refers to both the external characteristics of an instructional process and the internal characteristics of the learner, where the individual assumes primary responsibility for a learning experience. The remainder of this chapter will center on discussion of a model designed to further clarify this definition.

The PRO model: a framework for understanding self-direction in adult learning

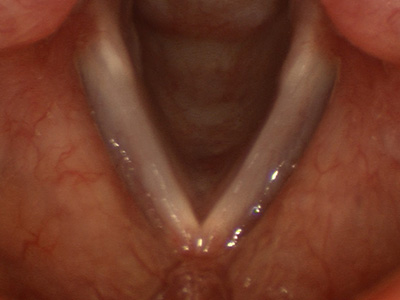

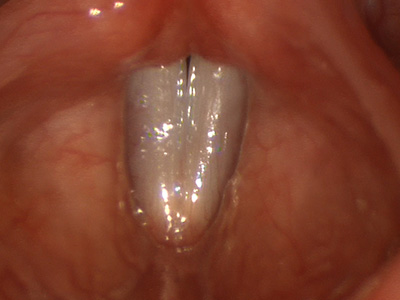

If the idea of self-direction in learning is viewed as comprising both instructional method processes (self-directed learning) and personality characteristics of the individual (learner self-direction), it is important to consider how these two dimensions are related. As a way of illustrating this relationship, we propose a model that distinguishes between these two dimensions while at the same time, recognizing that the two dimensions are inextricably linked to a broader view of self-direction. This model, which we refer to as the “Personal Responsibility Orientation” (PRO) model of self-direction in adult learning is designed to recognize both the differences and similarities between self-directed learning as an instructional method and learner self-direction as a personality characteristic. The model is not only intended to serve as a way of better understanding self-direction, it can also serve as a framework for building future theory, research, and practice. The major components of the PRO model, illustrated in Figure 2.1, are outlined below.

Figure 2.1: The “Personal Responsibility Orientation” (PRO) Model

Personal Responsibility as a Central Concept. As can be seen in Figure 2.1, the point of departure for understanding self-direction in adult learning, according to the PRO model, is the notion of personal responsibility. By personal responsibility we mean that individuals assume ownership for their own thoughts and actions. Personal responsibility does not necessarily mean control over personal life circumstances or environment. However, it does mean that a person has control over how to respond to a situation. As summarized by Elias and Merriam (1980), behavior “is the consequence of human choice which individuals can freely exercise” (p. 118). For instance, oppressed people typically lack control over their social environment; however, they can choose how they will respond to the environment. They can resign themselves to accepting the status quo or they can choose to act in a way designed to alter the current situation. In the latter case, while the outcome may not always be what is desired, the decision to act in a certain way reflects a choice not to willingly accept “the way things are.” Within the context of learning, it is the ability and/or willingness of individuals to take control of their own learning that determines their potential for self-direction.

Drawing largely on assumptions of humanistic philosophy, we base this emphasis on personal responsibility on two ideas. First, we embrace the view that human nature is basically good and that individuals possess virtually unlimited potential for growth. Second, we believe that only by accepting responsibility for one’s own learning is it possible to take a proactive approach to the learning process. These assumptions imply a great deal of faith and trust in the learner and, thus, offer a foundation for the notion of personal responsibility relative to learning.

Perhaps another way of understanding what we mean by personal responsibility can be found in the idea of autonomy, as discussed by Chene, who provides the following perspective: “Autonomy means that one can and does set one’s own rules, and can choose for oneself the norms one will respect. In other words, autonomy refers to one’s ability to choose what has value, that is to say, to make choices in harmony with self-realization.” (1983, p. 39)

Autonomy, as defined above, assumes that one will take personal responsibility, because one is independent “from all exterior regulations and constraints” (Chene, 1983, p. 39).

While we envision personal responsibility as the cornerstone of self-direction in learning, it is important to stress three related points. First, while we emphasize our commitment to the view that human potential is unlimited, we believe that each individual assumes some degree of personal responsibility. It is not an either/or characteristic. Thus, adult learners will possess different degrees of willingness to accept responsibility for themselves as learners. As was noted in the last chapter, it is a misconception to assume that learners necessarily enter a learning experience with a high level of self-direction already intact. Self-direction is not a panacea for all problems associated with adult learning. Nor is it always necessary for one to be highly self-directed in order to be a successful learner. However, if being able to assume greater control for one’s destiny is a desirable goal of adult education (and we believe it is!), then a role for educators of adults is to help learners become increasingly able to assume personal responsibility for their own learning.

Second, the emphasis on personal responsibility as the cornerstone of self-direction in learning implies that the primary focus of the learning process is on the individual, as opposed to the larger society. Yet, accepting responsibility for one’s actions as a learner does not ignore the social context in which the learning takes place. Such a view would be extremely short sighted. What personal responsibility does mean, however, is that the point of departure for understanding learning lies within the individual. Once this individual dimension is recognized, it is then important to examine the social dimensions that impact upon the learning process. And related to this point is a belief that one who assumes personal responsibility as an individual is in a stronger position to also be more socially responsible.

Finally, it is important to point out that in taking responsibility for one’s thoughts and actions, one also assumes responsibility for the consequences of those actions. As Rogers (1961, p. 171) has stated, to be “self-directing means that one chooses–and then learns from the consequences.” Within the context of adult education, Day (1988) has used fictional literature to illustrate this point. Drawing from the works Oedipus Rex, Martin Eden, Pygmalion, and Educating Rita, Day argues that adults are “decision-making beings” who are “ultimately responsible” for the decisions they make, that the “results of our learning experiences may as likely lead to discontent as to a state of well-being,” and that in general “learning produces consequences” (p. 125).

In conclusion, the notion of personal responsibility, as we are using it in the PRO model, means that learners have choices about the directions they pursue as learners. Along with this goes a responsibility for accepting the consequences of one’s thoughts and actions as a learner. The idea of personal responsibility will be further developed throughout the book, particularly in Chapter Seven, where the theoretical underpinnings of learner self-direction are explored.

Self-Directed Learning: The Process Orientation. Self-directed learning, as we have come to view the term, refers to an instructional method. It is a process that centers on the activities of planning, implementing, and evaluating learning. Most of the writings and research on self-directed and self-planned learning from the early and mid-1970s were developed from this perspective (e.g., Knowles, 1975; Tough, 1979). Similarly, the definitions of self-directed learning that we have used previously (Hiemstra, 1976a; Brockett, 1983a) stress this process orientation. Further, one of us (Hiemstra, 1988a; Hiemstra & Sisco, 1990) has described this as individualizing the teaching and learning process.

The process orientation of self-direction in adult learning focuses on characteristics of the teaching-learning transaction. Thus, when considering this aspect of self-direction, concern revolves around factors external to the individual. Needs assessment, evaluation, learning resources, facilitator roles and skills, and independent study are a few of the concepts that fall within the domain of the self-directed learning process. The illustrations compiled in recent books by Knowles and Associates (1984) and Brookfield (1985) exemplify this concept of self-directed learning as an instructional process in such areas as human resource development, continuing professional education, graduate and undergraduate study, and community education. Given the distinction between learning and education made earlier in the chapter, some readers may wish to think of this process orientation as “self-directed education.” We do not disagree with this term, but choose to refer to the process as “self-directed learning” in order to stress the link to the foundation laid by Knowles. Chapter Six offers a closer look at the process orientation of self-directed learning.

Learner Self-Direction: The Personal Orientation. While most of the work that has been seminal to the foundation of self-direction in learning has focused on the process orientation described above, the importance of understanding characteristics of successful self-directed learners has generally been stressed as well. For instance, Knowles (1970) identified several assumptions underlying the concept of andragogy as a model for helping adults learn. The first of these assumptions was that the self-concept of adult learners is characterized by self-direction, whereas dependence characterizes the self-concept of the child. Knowles (1980) later revised his view of pedagogy and andragogy from a dichotomy to a continuum. However, his emphasis on self-concept reflects the centrality of personality as an element of self- direction in learning. This emphasis on personality characteristics of the learner, or factors internal to the individual, is what we refer to as the “personal orientation” or learner self-direction.

Thus, in our view, learner self-direction refers to characteristics of an individual that predispose one toward taking primary responsibility for personal learning endeavors. Conceptually, the notion of learner self-direction grows largely from ideas addressed by Rogers (1961, 1983), Maslow (1970), and other writers from the area of humanistic psychology. Evidence of this personal orientation can be found in much of the research on self-direction in adult learning since the late 1970s. For instance, self-directedness has been studied in relation to such variables as creativity (Torrance & Mourad, 1978), self-concept (Sabbaghian, 1980), life satisfaction (Brockett 1983c, 1985a), intellectual development (Shaw, 1987), and hemisphericity (Blackwood, 1988). Learner self-direction is discussed further in Chapter Seven.

Self-Direction in Learning: The Vital Link. As we pointed out earlier, self-direction in learning is a term that we use as an umbrella concept to recognize both external factors that facilitate the learner taking primary responsibility for planning, implementing, and evaluating learning, and internal factors or personality characteristics that predispose one toward accepting responsibility for one’s thoughts and actions as a learner. The PRO model illustrates this distinction between external and internal forces. At the same time it recognizes, through the notion of personal responsibility, that there is a strong connection between self-directed learning and learner self-direction. This connection provides a key to understanding the success of self-direction in a given learning context.

It was noted in Chapter One that one of the myths related to self-direction in learning is that it is an “all-or-nothing” characteristic. In our view, both the internal and external aspects of self-direction can be viewed on a continuum. Thus, a given learning situation will fit somewhere within a range relative to opportunity for self-directed learning and, similarly, an individual’s level of self-directedness will fall somewhere within a range of possible levels. Related to this view of self-direction as a continuum is our belief that it is a mistake to consider high self-direction as ideal in all learning situations. As we have noted previously, because of “the great diversity that exists both in learning styles and in reasons for learning, it is extremely shortsighted to advance” the view that self-direction is the best way to learn and that instead, it is more desirable to think of self-direction as “an ideal mode of learning for certain individuals and for certain situations” (Brockett & Hiemstra, 1985, p. 33). It is this point that serves to link the concepts of self-directed learning and learner self-direction.

We suggest that optimal conditions for learning result when there is a balance or congruence between the learner’s level of self-direction and the extent to which opportunity for self-directed learning is possible in a given situation. If, for example, one is predisposed toward a high level of self-directedness and is engaged in a learning experience where self-direction is actively facilitated, chances for success are high. Similarly, the learner who is not as high in self-directedness is likely to find comfort and, in all likelihood, a greater chance of success in a situation where the instructor assumes a more directive role. In both instances, the chances for success are relatively high, since the learner’s expectations are congruent with the conditions of the learning situation.

Where difficulties and frustrations arise is when the balance between internal characteristics of the learner are not in harmony with external characteristics of the teaching-learning transaction. Individuals who enter a learning situation with a clear idea of how and what they wish to learn are likely to become frustrated and disenchanted if not given the freedom to pursue these directions. In the same vein, the learner who seeks a high level of guidance and direction will probably have similar feelings in a situation where the facilitator emphasizes an active leadership role by the learners. For individuals in either situation, the problem is that the teaching-learning situation is not in harmony with the needs and desires the learner brought to the situation. This does not mean that the learner was “unsuccessful,” nor that the facilitator was “ineffective.” Rather, it suggests that success and effectiveness are relative terms that depend on clear communication of needs and expectations among all parties engaged in the teaching-learning transaction.

The notion of learner self-direction, as an element of the PRO model, suggests a general tendency that exists to a greater or lesser degree in all learners. However, it is important to recognize that situational factors are often likely to impact on the type of instructional method a learner will seek. An adult who seeks to learn about current trends in real estate, for example, may be willing to relinquish control over the learning situation to the session leader for reasons of expedience or because of a personal lack of knowledge and experience in the real estate area. This does not diminish the learner’s level of self-direction; indeed, the decision to relinquish a degree of control was consciously made by the learner.

Several years ago, the first author attended a research conference where participants met to exchange information and ideas based on current research. The format for this conference, as is often the case for research conferences, was a series of paper sessions and symposia consisting of formal presentations followed by questions and discussions from the audience. In one symposium, the first presenter began by discussing some of the research trends in the topical area under consideration. However, about 20 minutes later, the second presenter began his portion of the symposium by asking participants to move their chairs into a circle so that it would be easier to “share ideas.” At least half of the group exercised a degree of self-direction by immediately leaving the room.

The above examples have been presented to illustrate two points. First, self-directed learning–the method that the second presenter was trying to implement–is not inherently the best method for adult learning. Although we believe that self-directed learning situations will most often be compatible with the needs, desires, and capabilities of adult learners, there are times when a highly teacher-directed approach will prove most effective and, indeed, will be expected and even demanded.

Second, when considering the fit between self-directed learning and learner self-direction, it is important to keep in mind that the congruence between these dimensions may at times be mitigated by factors such as the expectations of the learners. That symposium presenter must certainly have felt a degree of frustration and perhaps hurt as half of the audience walked out on his efforts to create a climate that most likely had served him very well in other settings. However, it is likely that the lack of congruence between his approach and the context in which the learning situation was taking place led to the exodus of so many participants. This brings us to a final element of the PRO model, which is a consideration of the social context in which self-direction in learning exists.

The Social Context for Self-Direction in Learning. The final element of the PRO model is represented by the circle encompassing the other elements. One of the most frequent criticisms of self-direction in learning has been an overemphasis on the individual, which is usually accompanied a failure to consider the social context in which learning takes place. Brookfield (1984c), for example, has suggested that by “concentrating attention on the features of individual learner control over the planning, conduct and evaluation of learning, the importance of learning networks and informal learning exchanges has been forgotten” (p. 67). In the PRO model, the individual learner is, in fact, central to the idea of self-direction. However, such learning activities cannot be divorced from the social context in which they occur. This point is further reinforced through discussions on the role of institutions in Chapter Eight and policy issues in Chapter Nine. We agree with Brookfield that social context is vital to understanding self-direction and that, to date, this concern has largely been overlooked. Brookfield’s (1981) own research, in which he found that “independent adult learners” often function as a “fellowship of learning” is a noteworthy exception to this gap in knowledge. One of the myths of self-direction identified in Chapter One is that such learning takes place in isolation. In order to truly understand the impact of self-direction, both as an instructional method and as a personality characteristic, it is crucial to recognize the social milieu in which such activity transpires.

Related to the social context are the political implications of self-direction in learning. Again, Brookfield (1984c) has helped to raise consciousness about the politics of self-direction. This, in turn, triggered the following response: “Brookfield’s comments are most insightful, for they force us to ponder the real consequences of situations where learners are truly in control of their learning. . . . many individuals, especially those who can be considered “hard-to-reach”, may believe that formal educational settings can reinforce conformity while stifling creativity. For such persons, institutions may be perceived as antithetical to the self-directed learning process. On a larger scale, these issues are amplified in situations where individuals view themselves as powerless in determining the direction of their lives. What are the potential consequences. . . of promoting self-direction in societies where individual human rights may be in question? Clearly, the issue of control is a crucial one because, ultimately, it must move beyond the individual dimension into the social and political arenas.” (Brockett, 1985c, p. 58)

Thus, while the individual is the “starting point” for understanding self-direction in adult learning, the social context provides the arena in which the activity of self-direction is played out. In order for us to truly understand the phenomenon of self-direction in adult learning, it will be crucial to recognize and deal with the interface between these individual and social dimensions. Chapters Eight and Ten address the social context from institutional and cross-cultural perspectives, respectively.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have attempted to alleviate some of the confusion surrounding the meaning of self-direction and related concepts. By proposing the Personal Responsibility Orientation model, we are suggesting that in order to understand the complexity of self-direction in adult learning, it is essential to recognize differences between self-directed learning as an instructional method and learner self-direction as a personality characteristic. These two dimensions are linked through the recognition that each emphasizes the importance of learners assuming personal responsibility for their thoughts and actions. Finally, the PRO model is designed to advance understanding of self-direction by recognizing the vital role played by the social context in which learning takes place. Moving to a critical examination of research on self-direction in the next two chapters, the remainder of the book is designed to further illuminate the ideas expressed in the PRO model.

Full details of the references can be found at: http://home.twcny.rr.com/hiemstra/sdilbib.html.

To cite this chapter: Brockett, R. G. and Hiemstra, R. (1991) ‘A conceptual framework for understanding self-direction in adult learning’ in Self-Direction in Adult Learning: Perspectives on Theory, Research, and Practice, London and New York: Routledge. Reproduced in the informal education archives: http://www.infed.org/archives/e-texts/hiemstra_self_direction.htm